Ursula K. Le Guin was of course immensely important to science fiction, and beyond that to literature. The wider world of letters has recognized her significance a little bit in the last few years, with the Library of America volumes, and with the National Book Award. Within the SF community she’d been recognised and appreciated for much longer. She was the first woman to win a Best Novel Hugo, for The Left Hand of Darkness in 1969, and the first woman to win it twice, with The Dispossessed in 1974. She widened the space of science fiction with what she wrote. She got in there with a crowbar and expanded the field and made it a better field. She influenced everybody who came along afterwards, even if it was a negative influence of reacting against her. Delany wrote Triton to argue with The Dispossessed. And all of us who grew up reading her were influenced. Even people who have never read her have been influenced by her secondary influence, in terms of how much more it’s possible to do because she broke that ground.

We all remake our genre every time we write it. But we’re building on what’s gone before. Le Guin expanded the possibilities for all of us, and then she kept on doing that. She didn’t repeat herself. She kept doing new things. She was so good. I don’t know if I can possibly express how good she was. Part of how important she was, was that she was so good that the mainstream couldn’t dismiss SF any more. But she never turned away from genre fiction. She continued to respect it and insist on it being respectable if she was to be seen so.

She’s even greater than that. You know how some people get cranky when they get old, and even though they used to be progressive they get left behind by changing times and become reactionary? You know how some older writers don’t like to read anything that isn’t exactly the same as people were writing when they were young? You know how some people slow down? Ursula Le Guin wasn’t like that, not at all. Right up to the moment of her death she was intensely alive, intensely involved, brave, and right up to the minute with politics. Not only that, she was still reading new things, reviewing for The Guardian, writing perceptive, deeply thought pieces about books by writers decades younger. She kept on going head to head with mainstream writers who said they weren’t writing genre when they were—Atwood, Ishiguro—and attacking Amazon, big business, climate change, and Trump. Most people’s National Book Award pieces are nice bits of pablum, hers was a polemic and an inspiration. I emailed to say it was an inspiration, and she told me to get on with my writing, then. I did.

She was immensely important to me personally. I loved the Earthsea books as a child. The Dispossessed was the first adult SF book I read. I’ve been reading her for three quarters of my life. Her way of looking at the world had a huge influence on me, not just as a writer but as a human being. I wouldn’t be the same person if I hadn’t discovered her work at the age I did. And as I sit here stunned to think she’s dead, I’m comforted a little that at least she knew how much she meant to me. It’s very difficult to tell the authors you love how much you love their work, how important they are to you. I didn’t do that, on the one occasion I met her, at the Ottawa Literary Festival. I just stammered, like everyone does in that situation. I did tell her how excited I was that she blurbed Farthing, but that’s as far as I could get. But she did know, even though I couldn’t say it directly, because she read Among Others. She wrote me a lovely email about how she couldn’t blurb that book because she was in a way a character in it, which of course, in a way, she was. She gave me permission to use the “Er’ Perrehnne” quote at the beginning of the book, and the alien at the end. She wrote a wonderful essay about it (about my book!), part of which appeared in The Guardian and all of which appeared in her Hugo-winning collection Words Are My Matter, where I was awestruck to find it as I was reading it. She didn’t write about what most people have written about when talking about that book. She wrote about the magic system. She understood what I was trying to do. But reading it, she also knew how much she meant to me. I can’t look at that email again now. But I treasure it, along with all the email she ever sent me.

I can’t believe she’s dead. But at least she led her best life, excellent right up to the end, brave and honest and passionate and always completely herself.

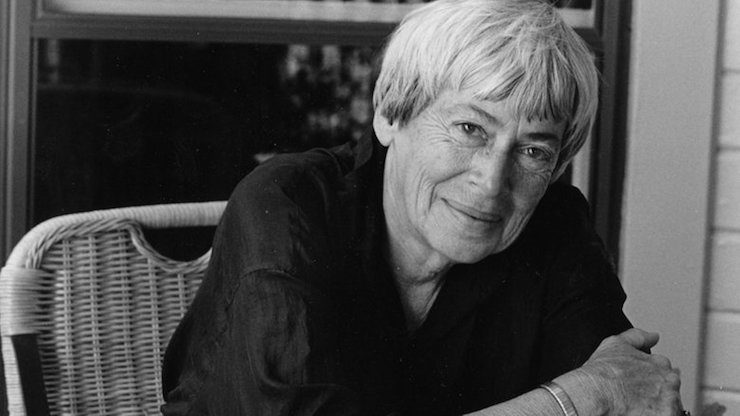

That one time I met her, I had my son with me. He was seventeen or eighteen at the time. She sat there at the front of the packed room, being interviewed, and reading from Lavinia. She was tiny and wrinkled and ancient, and everything she said was wise and challenging and astute. “She is a Fourth,” my son said, referring to Robert Charles Wilson’s Spin, where some people go on to have a Fourth age of life, an epoch of wisdom. Not only did he instinctively see her in science fictional terms, but Spin itself is a book that wouldn’t have been possible without her influence. If she’d really been a Fourth, she’d have had another seventy years of life. I wish she did. But since she doesn’t, it’s up to us to write, oppose, encourage, speak out, build, and pass forward what we can.

I spent this morning reading a brilliant first novel by a woman writer. Then I did an interview about my new collection. Then I spent the rest of the afternoon writing a poem into the female spaces in Prufrock. I am living my life in the world Ursula K. Le Guin widened for me.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published a collection of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections and ten novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her most recent book is the collection Starlings. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.